Case 2 of 6 [1]

[View PDF]

Torex Gold Resources Inc. is a Canadian gold mining company which trades on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX), is incorporated in British Columbia and has corporate offices in Toronto, Ontario. The Media Luna project is wholly owned by the company and located in the state of Guerrero, Mexico.

Summary

- On November 3, 2017, approximately 600 workers from Torex Gold’s Media Luna mining facility, located in the Mexican state of Guerrero, carried out a work stoppage to demand their right to be represented by an independent union of their own choosing. The workers alleged that the union at the facility, known to be unrepresentative and to use intimidation tactics, had been chosen for them by the employer without their prior knowledge or consent and did not represent their interests.[2]

- A series of violent events ensued, endangering workers and community members protesting outside of the mine; four individuals, formerly employed by the company[3] and associated with the worker struggle, were killed. Workers were eventually deterred from continuing to protest due to the fear of violent reprisals.

- On April 6, 2018, the company resumed operations before the labour dispute was resolved. To date, notwithstanding the protests of workers at the mine, the protection contract union continues to hold legal title to representation at the facility. Investigations into the four deaths remain unresolved.

The Detail

The state of Guerrero, Mexico has been highlighted as among the most dangerous states in the country.[4] Violent deaths in this state, linked to Canadian mining companies, have been well documented.[5] In the case of Torex, the Justice and Corporate Accountability Project reports five separate incidences of criminalization of protest between 2009 and 2015, including irregular arrests and violent attacks against opponents to the mine, and the alleged murder of an engineer said to have been doing business with the company.[6]

Mexico is known to have a corrupt and anti-democratic labour relations system where protection contracts – bogus collective agreements – are signed between unrepresentative unions and employers often before any workers have been hired at a plant and therefore without workers’ prior knowledge.[7] The Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM) and other ‘official unions’ are considered to be company unions which represent the employers’ interests over the workers. One of the demands throughout the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) negotiations, which took place alongside the events in this case, was the need to strengthen Mexico’s labour standards. Ending the practice of ‘employer protection contracts’ was considered essential to promoting freedom of association and improving wages.[8]

On November 3, 2017, approximately 600 workers from Torex Gold’s Media Luna mine participated in a work stoppage and protest to demand better wages and their right to choose an independent union rather than one imposed on them at the mine. The CTM ‘protection union’ at the facility was chosen by their employer, Torex Gold Resources Inc. without workers’ prior consent.[9] Workers alleged that they were forced to sign the CTM union membership, and were threatened that they would lose their jobs if they refused.[10] Torex’s Vice President admitted in an interview that the company had ‘engaged CTM’ before hiring workers.[11] In response to this case study, the company said it “encouraged the matter to be resolved through a government sanctioned process for the Company [sic]’s workers to vote on their preferred union”.[12]

Neighbouring communities who joined the protest argued that the company was failing to compensate them for its use of water[13] and raised concerns about irregularities in how land had been acquired by the company from the original occupants.[14]

Ten days into the work stoppage, the company had still not entered into dialogue with the workers. Instead, the workers were notified by representatives of the state and the Labour Secretary that they had to end the work stoppage before there could be dialogue with the company and relevant authorities.[15] Meanwhile, Mexican authorities deployed 130 federal police officers at the mine,[16] and a security check point was set up nearby.[17] Despite these pressures, the protest continued.

On November 18, 2017, two brothers who had participated in the work stoppage, Victor and Marcelino Sahuanitla Peña, were shot and killed. Consistent with state authorities’ propensity to blame instances of political violence on gang activity, local police argued that the deaths were a result of an altercation between “rival militias” and therefore not related to the labour dispute.[18] Torex Gold also asserted that the killings were unrelated,[19] and that the two were not employees of Torex.[20] However, three years later, the company admitted that the brothers, as well as two other individuals who were involved in the work stoppage and were subsequently murdered, were all former employees of the mine and likely targeted as a result.[21]

While initially supporting the workers’ request for a union vote to take place,[22] the company did not wait for the Mexican state to finalize a date or for the labour dispute to be resolved.[23] On January 15, 2018, they reinitiated operations.[24] The Mexican labour authorities, widely criticized for their bias toward the ‘official’ unions,[25] like the CTM, did not fulfill their responsibility to set the date, despite holding two public hearings to this end.[26] Less than two weeks later, on January 24, labour activist Quintin Salgado was killed. The week prior to his death, while on his way to a meeting with striking workers from the mine, he was beaten and threatened to stop his work advocating for new union representation.[27]

Less than three months later, on April 6, 2018, Torex announced that the ‘illegal’ blockade had ended, noting that the next stage in the union dispute was to wait for the Federal Labour Board to designate a date for the vote to take place.[28] To date, however, the CTM union continues to hold the union representation at the mine. According to the workers, organized crime, allegedly acting in support of the company, issued death threats if the stoppage did not end.[29] On May 12, 2020, a fourth labour campaigner, Óscar Ontiveros Martínez, was allegedly murdered by organized crime near the Torex mine.[30] The 29-year-old had been involved in the 2017 events and was considered to be a ‘promising figure’ in the Mexican labour rights movement.[31]

In an email reply to a draft of this case study, a representative of Torex Gold said “we have a very positive and productive relationship with our employees and the CTM union” and that “operating responsibly is in the DNA of our Company; we would never condone, or be a party to, the kind of radical behaviour, threats and violence that the Company is accused of.”[32]

Reaction from Canadian and international organizations

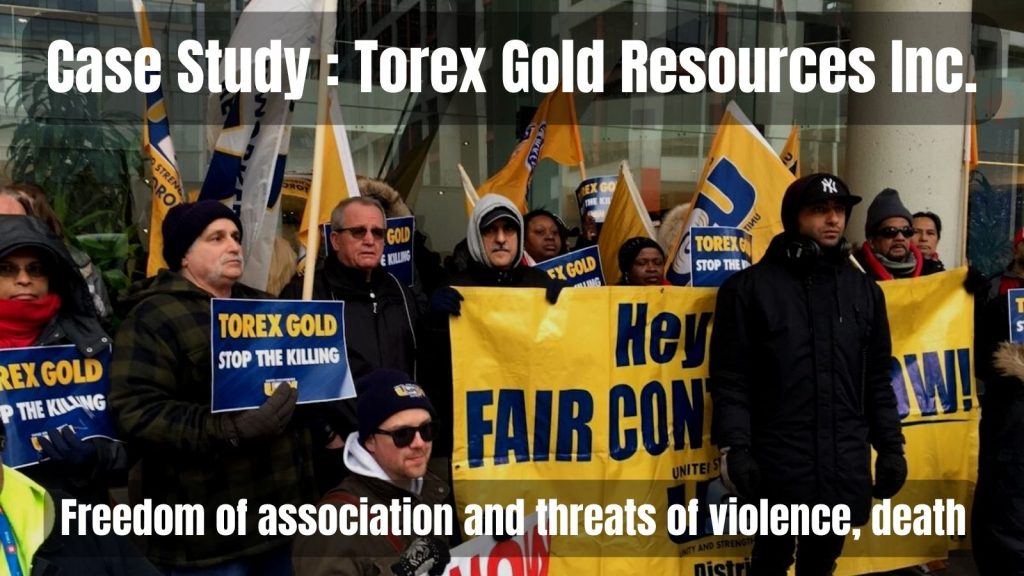

During the height of the work stoppage, international labour rights groups, including the United Steelworkers and UNIFOR, sounded alarms about the violence and their concern for workers’ safety. Letters were written to Employment and Social Development Canada’s Bilateral and Regional Labour Affairs office, to the Prime Minister and to the Minister of Foreign Affairs to intervene with the Mexican government. Various press releases and news coverage circulated. While the Government of Canada did communicate with Torex, Canada was unable or unwilling to undertake actions that would have led to the protection of workers’ right to freedom of association or to fully investigate the deaths or prevent ongoing violence.

What if…?

If mandatory human rights due diligence legislation was in place, what would be different for the workers at Torex Gold’s mine?

- Workers’ right to democratically choose their union representation would have been protected, and workers’ safety and lives could have been safeguarded.

- If those rights were not protected by Torex and lives were jeopardized, as was the case at the Torex facility, workers or their allies could have sought justice in a Canadian court.

How?

Throughout the operational life of a project, mining companies like Torex would have to identify and assess the human, environmental and labour rights risks at their operations, prevent and mitigate impacts to workers’ rights, and account for how they address those impacts.

- IDENTIFY and ASSESS: If Torex had undertaken an adequate risk assessment it would have identified:

- The high risk of labour rights violations that may result from developing a relationship with a known ‘protection’ union

- The high risk of violence and corruption in the state of Guerrero which create barriers to freedom of association and make the right to protest unsafe for workers

- PREVENT, MITIGATE, ACCOUNT FOR: Torex could have taken steps to ensure workers’ right to choose their union representation was respected and ensure the safety of its workers by:

- Considering and documenting how it intended to ensure the protection of its workers and their rights given the risks of operating a mine in one of the country’s most violent states

- Developing robust labour relations and freedom of association mechanisms that ensure the company effectively engages in ongoing dialogue with workers and that labour rights are protected

- Incorporating an alert mechanism to notify the company of labour rights violations, and addressing any violations as soon as they are identified

- Justice could have been accessed for workers

- If affected workers, labour unions, or human rights organizations had had effective access to remedy, they would have had the right to sue Torex in a Canadian court. The courts would assess the adequacy of Torex’s due diligence procedures and, if it was determined that Torex failed to follow through on its own due diligence measures or those measures were considered to be weak and ineffective, Torex would have been held liable for harm.