Case 6 of 6 [1]

[View PDF]

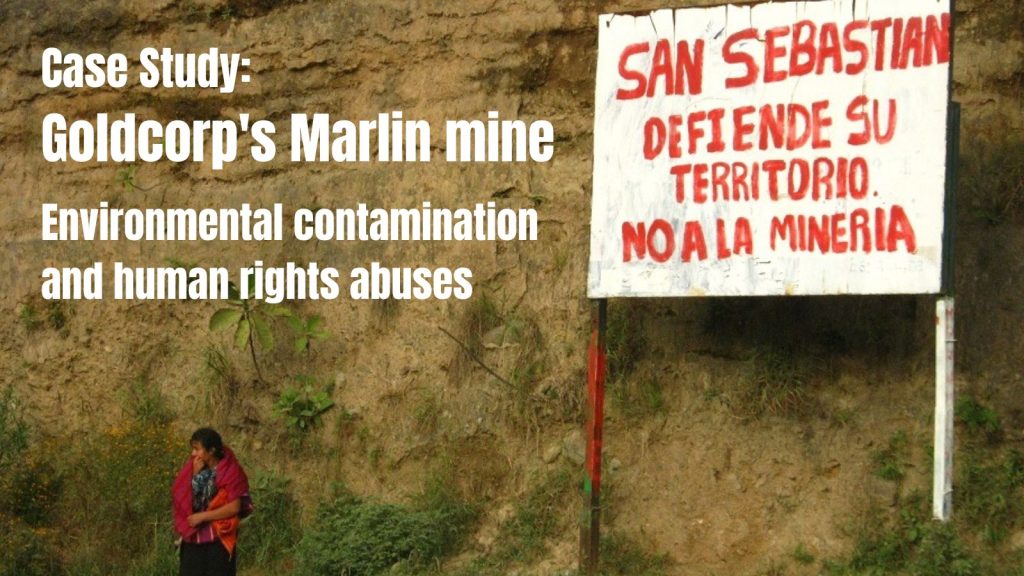

The Marlin gold and silver mine is located in northwestern Guatemala straddling the municipalities of Sipacapa and San Miguel Ixtahuacán, San Marcos.[2] Between 2005 and 2017, it was operated and wholly owned by Montana Exploradora, a subsidiary of Canadian mining company Glamis Gold Ltd.[3] In 2006, it was purchased by Canadian mining giant Goldcorp Inc. Goldcorp’s headquarters were located in Vancouver and the company was registered on the TSX. Mine closure and reclamation began in June 2017,[4] and the company was acquired by Newmont Corporation in 2019.

Summary

- Since receiving its first permit in 2003, the project received strong community opposition from the largely Indigenous Mayan population. Concerns raised at the local, national and international levels addressed the failure to consult the local population, deceptive public communications about the project, impacts on local water sources, and increased violence and conflict in the area around the mine.

- In 2010, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), part of the Organization of American States, of which both Canada and Guatemala are members, called for the suspension of the mine; however, the Guatemalan government ultimately did not comply and Goldcorp continued to operate, despite ongoing opposition and mounting evidence of potential environmental contamination.

- According to well-documented allegations made in 2017 by the San Miguel Defense Front, an active community-based group, the mine’s operations have caused 10 water springs to disappear; 500 families’ homes to sustain cracks in infrastructure; and skin impacts in children from allegedly contaminated water.[5] To this day, some community members do not have access to potable water.

- The mine closed in June 2017 with remediation efforts slated for completion by the end of 2020 and Newmont Gold officially leaving in 2026. Civil society groups report that at the time of the closure, Goldcorp had only completed 24 of the 42 recommendations for mine closure outlined in its own 2010 Human Rights Assessment,[6] a clear example of the failure of non-binding human rights reporting mechanisms.

- Both Goldcorp’s and Newmont’s opacity related to the closure process and the lack of government oversight pose an ongoing risk to impacted communities, who have been left to deal with the long-term environmental impacts.[7]

The Detail

In January, 2005, Raul Castro Bocel was fatally shot and at least 20 others injured when approximately 1,200 soldiers and 400 police officers opened fire on unarmed protesters.[8] For 40 days, the protesters had been blocking the passage of mining equipment destined for the Marlin mine. It was clear that the government’s intention was to protect this investment, at all costs, while ignoring concerns about potential environmental harm from local opposition.

Communities reject Marlin mine

When Goldcorp Inc. acquired the Marlin mine in 2006, the project had already elicited a number of concerns from the largely Indigenous neighbouring population,[9] including the Guatemalan government’s failure to consult the Indigenous population affected by the mine. In June 2005, the Municipality of Sipacapa held a plebiscite to address the lack of consultation, voting almost unanimously against the mine.[10] Glamis Gold filed an injunction against the vote, which was denied; however, legal action initiated by the Ministry of Energy and Mines days before the vote resulted in a May 2007 Constitutional Court decision that the results were not legally binding and as a result insufficient to halt the mine’s operations.[11] The Marlin mine therefore continued operating, despite local rejection, and for over a decade became a focal point for local and national opposition to Canadian mining in Guatemala.[12] Violence and tension heightened especially between 2005 and 2011 resulting in at least four deaths and dozens of injuries. Given the high rate of impunity in the country, these incidents were never fully investigated.[13]

Meanwhile, dozens of arrest warrants were filed against community leaders and protesters.[14]

Formal attempts to raise concerns about the mine

As evidence of the mine’s potential harms on local water supplies mounted,[15] community members and allies initiated a number of formal processes at international levels, including a complaint to the International Finance Corporation’s Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, in 2005;[16] and a 2009 Request for Review with the Canadian National Contact Point for the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),[17] among others. None of these processes, however, led to an independent investigation.

Finally, on May 20, 2010, the IACHR responded to a 2007 petition from 13 communities near the mine, which was then extended to additional communities. It called on the Guatemalan government to suspend the mine’s operations; implement a number of measures to prevent environmental contamination, and attend to health and safety concerns.[18] Following a visit to Guatemala one month later, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of Indigenous People, James Anaya, urged the Guatemalan government to act on the IACHR’s guidelines and to conduct an investigation into allegations that the Marlin mine was adversely impacting Indigenous peoples.[19]

In a move that sparked national and international outrage, the Guatemalan government ultimately decided not to adhere to the IACHR guidelines and refused to suspend the mine.[20] The government justified its decision through an ‘administrative review’ that it conducted, which included an alleged review of 23 studies that were never made public – demonstrating a clear lack of transparency.[21] For its part, Goldcorp had embarked on its own Human Rights Assessment (HRA) back in 2007, which was released three days prior to the IACHR’s response, on May 17, 2010. The HRA also called for a “halt” to activities, cited various human rights abuses and noted a “systemic failure to address grievances in the communities.”[22] It also found that water quality reports from government regulators failed to provide conclusive evidence about the potential health impacts of the mine. Despite these findings, the company failed to implement various of the report’s key recommendations, in particular halting further land acquisitions, exploration, and mine expansion.[23] Subsequently, in December 2011, the IACHR lifted its suspension order and instead required that Goldcorp adopt the necessary measures to ensure that the neighbouring communities have access to potable water.

Reaction from international and Canadian organizations

Since 2004, international organizations and solidarity networks have been closely following developments at the Marlin mine, raising countless alarm bells. In Canada, they have penned urgent actions[24] to Guatemalan and Canadian officials, written reports, and met on numerous occasions with Canadian Members of Parliament and Global Affairs Canada staff in both Ottawa and Guatemala. Goldcorp’s own shareholders presented resolutions calling for the suspension of the mine in 2008 and 2011[25] due to concerns related to the violation of the right to free, prior and informed consent and increased violence and environmental risks, and another one in 2012 calling on the company to increase its water remediation budget for mine closure from US$2 million to US$30 million due to concerns related to long-term health impacts on communities.[26] None of these actions, however, deterred operations at the mine. In a response to a 2014 Amnesty International letter of concern regarding ongoing tensions, Goldcorp stated that the company did not believe “significant tension persist[ed]” and blamed any ongoing resistance on “outsiders” to the community and misinformation campaigns.[27] Canadian organisations launched a judicial review seeking access to information regarding the role of the Canadian government in this saga.[28]

What if…?

If mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence legislation was in place, what would be different for the communities impacted by GoldCorp’s Marlin mine in Guatemala?

- The company would have been legally required to respect community members’ right to free, prior and informed consent, to a healthy, safe and sustainable environment – including to potable water – and to be free from violence and bodily harm.

- If those rights were ignored by Goldcorp, community members and their allies could have sought justice in a Canadian court.

- Impacted communities would not have to rely solely on the possibility that the Government of Guatemala – itself subject to allegations of corruption – would finally be moved to provide compensation and access to potable water after years of local organizing. They would have had a legal right to access justice in Canada to make a claim for compensation for the harm they suffered.

How?

Goldcorp would have been obliged to put in place measures to ensure respect for human rights and the environment throughout its global operations and supply chains and to carry-out risk-based due diligence to identify, prevent, cease, mitigate and account for the risk of adverse impacts on the environment and human rights by its subsidiaries.

IDENTIFY AND ASSESS:

If Goldcorp had undertaken an adequate risk assessment it would have identified:

- the Guatemalan government’s history of systemic violence and discrimination against the Indigenous Mayan population, especially in relation to mining and hydroelectric projects,[29] and therefore the high risk that the Guatemalan government would not properly consult the impacted communities prior to approving a mine permit and that operating the mine despite local opposition could lead to social unrest, violence and human rights abuses;

- that the lack of transparent environmental monitoring makes it difficult for communities to access information about the mine’s potential impacts, and access remedy for long-term environmental harm and health impacts; and

- it could have identified the need for an independent human rights impact assessment and ensured that any findings from similar key reports related to human rights and environmental impact were made available and accessible to impacted communities.

PREVENT, MITIGATE, ACCOUNT FOR:

Goldcorp would have had to take steps to ensure the prevention of serious negative impacts to the environment, human rights and the long-term health of communities surrounding its Marlin project, for instance by:

- using its leverage with the Guatemalan government to ensure communities were properly consulted according to international and customary law;

- establishing regular independent and transparent human rights and environmental monitoring and meaningful accountability mechanisms; and

- remedying harms that occurred by paying to repair damages allegedly caused by its subsidiary’s operations (e.g. the costs of repairs to homes, health treatments, infrastructure to provide access to potable water and/or to ensure safe and thorough closure procedures are instituted).

Goldcorp would have had to establish policies and procedures to mitigate future risk, including:

- ensuring the establishment of a monitoring and oversight body to ensure compliance with the recommendations of its own Human Rights Assessment process, or ensuring from the outset that the HRA was fully independent.

If Goldcorp failed to take concrete steps to prevent or mitigate abuses, community members or human rights and environmental organizations that support them could have sought justice in a Canadian court, and Goldcorp would have had to account for and defend the steps it had taken to prevent harm caused by its subsidiary.

The adequacy of Goldcorp’s due diligence procedures would be held to account, such as its:

- failure to halt operations in response to wide scale opposition that resulted in death, injury and other harms against the Indigenous population and community leaders;

- failure to put in place proper environmental safety measures despite significant evidence pointing to the risk of environmental harms including contamination of water sources and decreased access to clean water supplies and / or failure to halt operations if prevention and mitigation measures were insufficient; and its

- failure to establish reasonable mitigation measures such as proper mine closure and sufficient financial compensation to local communities for the costs of environmental remediation.